Event report

December 16, 2025

FabCafe Global Editorial Team

When we talk about “space,” what comes to mind? Satellites, rockets or billionaires taking joyrides?

As research advances, space is no longer the exclusive domain of aerospace engineers and scientists. It has evolved into a future arena requiring interdisciplinary talent from fields such as architecture, biology, medicine, design and engineering.

In The Future of Space: A 2040 Vision, we hosted three speakers with distinct backgrounds: Cecilia Tham, founder of Futurity Systems; Miki Sode, a former commercial innovation program manager for the International Space Station (ISS); and Luciana Tenorio, a PwC consultant with experience in architecture and space research.

Leveraging their cross-disciplinary expertise, the three speakers led a dialogue covering the space economy, food, governance and human adaptation. Together, they reimagined the future of space in 2040 and explored how it connects to daily life on Earth.

|

Project Apophis

Launched by Loftwork, FabCafe, and the Chiba Institute of Technology, Project Apophis is the first Japan-U.S. private-led asteroid exploration initiative. Seizing the rare opportunity of Apophis’s close approach in April 2029, the project aims to deploy a satellite to observe the asteroid. It combines scientific exploration with a platform for cross-industry co-creation. Notably, the project collaborates with Safecast to leverage open data and citizen science for deep-space exploration. |

What will the space economy look like in 2040?

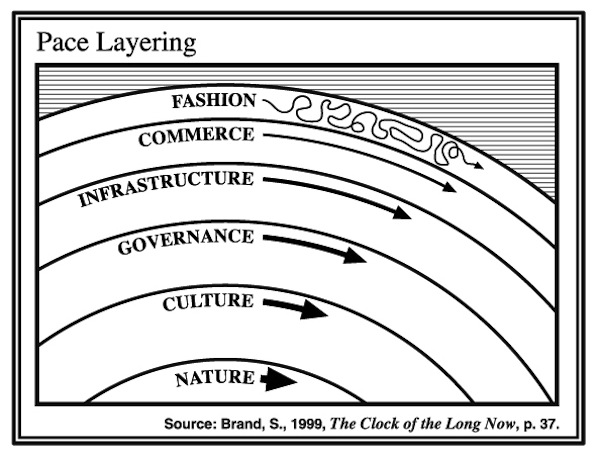

Starting from a societal perspective, Tham used Stewart Brand’s “pace layers” model to reframe space development. Space development is not just about technology. It involves deeper shifts in culture, language, economics and policy.

When we see the wealthy riding rockets, it is easy to misinterpret space as elite entertainment. However, these early, expensive stages often serve as the starting point for mass adoption. This mirrors how electric vehicles were once affordable only to a few but are now becoming mainstream.

Tham also warned that language subtly influences our vision of the future. Words like “colonization” are deeply tied to historical contexts of power and exploitation. If we continue to use such terminology, we risk carrying those same power dynamics into outer space. She argued that space requires a new vocabulary and governance framework to avoid repeating Earth’s history.

Dining in Space: From lettuce and recycled coffee to ”Cosmovores“

Food remains the most human aspect of life in space. Sode noted that resource circularity is a major priority on the International Space Station. Water resources are almost entirely recycled. She shared that astronauts say “today’s coffee is yesterday’s coffee”.

Tenorio experienced a different kind of extreme survival inside a simulated Mars base. Crew members subsisted on greenhouse-grown lettuce, quinoa, and potatoes mixed with powdered eggs and dried goods. She laughed, saying that her first stop upon returning to civilization was a fast-food restaurant. The experience taught her that the challenge of space food goes beyond nutrition. It also involves satisfying visual and psychological needs.

Space food design is evolving to address these psychological demands. Astronauts now have access to microwaves and zero-gravity ovens. The ISS crew has even successfully baked chocolate chip cookies. Crews often rely on Taco Night and communal meals to boost morale and celebrate various cultures gathered on the ISS. Tenorio emphasizes that the appearance and texture of food are crucial for maintaining mental health.

Sode sees great potential in synthetic biology for the future. One day, she said, we might use microbes to produce essential nutrients in resource-scarce environments. This could make the Replicator from Star Trek a reality. Building on the idea of new terminology, Tham joked that we might soon use the term “cosmovore.” The evolution of space dining spans everything from nutritional engineering to psychological comfort. It is ultimately a profound exploration of how humans maintain a nutritional balance as well as a sense of normalcy in extreme conditions.

The Replicator seen in StarTrek might one day become a reality? (Image credit: Star Trek)

How do humans become “people of space”?

Tham broached a possibility for a future where CRISPR gene editing may be used to modify the bodies of astronauts to be more suitable for the extreme space environment. However, Sode argued that dreams of gene editing are premature. Gene-editing and its (long-term) consequences are yet to be explored/elucidated more on Earth; We still do not fully understand the effects of the full spectrum of gravity – from microgravity to the moon’s gravity (one-sixth of Earth’s) or Mars’ gravity (one-third of Earth’s) – on our biology.

The real challenges are less romanticway more practical. Spacesuits are heavy and difficult to put on, and toilet designs are still less than ideal. Isolation impacts sleep and emotional well-being, and team dynamics can become fragile in confined environments. These issues are more urgent than enhancing physical abilities.

Regarding space architecture, Tenorio said the goal is not to build sci-fi bases. Instead, the focus is on creating places where humans can live safely, comfortably and with psychological stability. This design work is far closer to human needs than rocket science.

Soap bubble satellites and gas stations in space

Discussing exciting concepts, Tenorio shared an idea from a workshop she attended: the “soap bubble satellite.” This concept envisions using extremely thin membranes and bubble-like forms to create large-scale structures capable of unfolding in space. While currently just a concept, it highlights the challenges of material strength and structural stability when scaling up.

Sode shared a concept being developed by a startup OrbitFab: building a “gas station in space.” Following the role of gas stations along interstate roads in the development of local economies as a metaphor, the idea suggests that establishing supply nodes could shape future orbital economies. Current research focuses on storing and transferring water or propellants in microgravity.

From left: Special guest Luciana Tenorio, Miki Sode and Cecilia Tham

Inclusion and openness in space

Limitations on Earth can transform into possibilities in space.

Sode highlighted the European Space Agency’s “parastronaut” project. In a microgravity environment, many conditions viewed as physical disabilities on Earth are not necessarily limitations. Consequently, the ESA has selected John McFall, a paralympian with an amputated right leg, as the first parastronaut. This marks a significant step toward inclusivity.

Addressing emerging nations not directly involved in space programs, Sode noted that the United Nations Office for Outer Space Affairs, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA), and others are working towards lowering barriers. These initiatives give more countries the opportunity to participate in space experiments and utilize satellite data.

Through the speakers’ insights demonstrate that conditions considered limitations on Earth can, conversely, present certain advantages in space. Space research is moving in a more open and diverse direction.

John McFall was selected in 2022, becoming the first person with physical disability to be a member of the European Space Agency’s astronaut reserve. (Credit: ESA/Novespace)

Would you go to space if money were no object?

Cecilia ended the discussion with a seemingly lighthearted question that stirred the imagination of the room.

“How many of you would want to go to space if we could travel today?”

“How many of you guys would go to Mars knowing that you could never come back to Earth?”

Faced with this extreme choice, some raised their hands in excitement. Others hesitated. The point was not to find a standard answer. Instead, it served as a lingering thought to end the session. It invited everyone to reflect on a near future where space travel is within reach. Will we choose to forge ahead actively, or will we conservatively wait and watch?

The space of 2040 may be more human than we imagine

The evening was not merely about rockets or science fiction. It was a dialogue that interrogated the relationship between space and humanity. The speakers reminded us that space research has transcended technology. It is shifting from a stage for scientists into an experimental field where culture, psychology, and ethics converge.

Moreover, research in space may happen in a vacuum, but it certainly doesn’t stay there. Sode cited her experience researching bone loss in microgravity at NASA as an example. She explained that space allows us to observe bodily changes in unique environments more rapidly. This research then returns to Earth, helping us understand aging and osteoporosis. Insights made miles above our heads can make it back to hospitals, factories, and laboratories back on terra firma.

Ultimately, exploring space is not about distancing ourselves from Earth. As we explore the universe, we can learn how to better live on this planet.

At FabCafe Tokyo, we actively develop programs and events focused on the future, technology and cross-disciplinary innovation. We also offer consultation for workshop design and project planning that bridge the gap between science, art and business.

Please feel free to contact us.

-

FabCafe Global Editorial Team

This articles is edited by FabCafe Global.

Please feel free to share your thoughts and opinions on this article with us.

→ Contact usThis articles is edited by FabCafe Global.

Please feel free to share your thoughts and opinions on this article with us.

→ Contact us