Project Case

March 25, 2024

Kakeru Asano

Design Researcher

ELEMUS LLC (based in Okazaki City, Aichi Prefecture, Japan) manufactures and sells Sustimo®, a biomass molding material entirely made from plant-based resources. It is made mainly from finely ground wood powder and urushi sap using a patented technology (PAT No. 3779290) spearheaded by the Tokyo Metropolitan Industrial Technology Center (urushi refers to natural lacquer from the Asian lacquer tree). With physical strength and heat resistance almost rivaling ABS resin, Sustimo® is rapidly attracting attention as a new material for a sustainable society.

Is Sustimo® really just an alternative to petroleum-based plastics and other environmentally hazardous resources? ELEMUS CMO Takamasa Inaki sees potential for much more and is already working with Okazaki City to develop urushi forests.

In September 2023, Hidakuma, together with designer duo Kaori Akiyama (STUDIO BYCOLOR) and Yasuhiro Horiuchi (TRUNK DESIGN Inc.), launched the Sustimo Lab Project to explore the possibilities of regenerative materials, aiming to realize the future envisioned by ELEMUS.

This project report will be presented in three installments, with the first providing an overview of Sustimo® developed by ELEMUS as well as a report on the project team’s field research in Joboji, Iwate Prefecture, which is one of Japan’s largest urushi production areas.

Written by Kakeru Asano | Photos by Kentaro Saito, Mizuki Imai, and Kakeru Asano

On April 1, 2022, Japan introduced the Act on Promotion of Resource Circulation for Plastics in response to ongoing global environmental issues such as the problem of marine plastic waste as well as climate change. Until recently, Japan has incinerated most recovered waste plastic, with its recycling utility limited to the generation of thermal energy. Now, the Japanese government has set a goal of reducing one-way plastic disposal by 25% by 2030 and significantly increasing the percentage of recycled and biomass plastics in circulation. Regardless of domestic or international concerns, there is an urgent need for the economy to shift from linear to circular. In response, material manufacturers worldwide are aiming to be at the forefront by actively engaging in research and development.

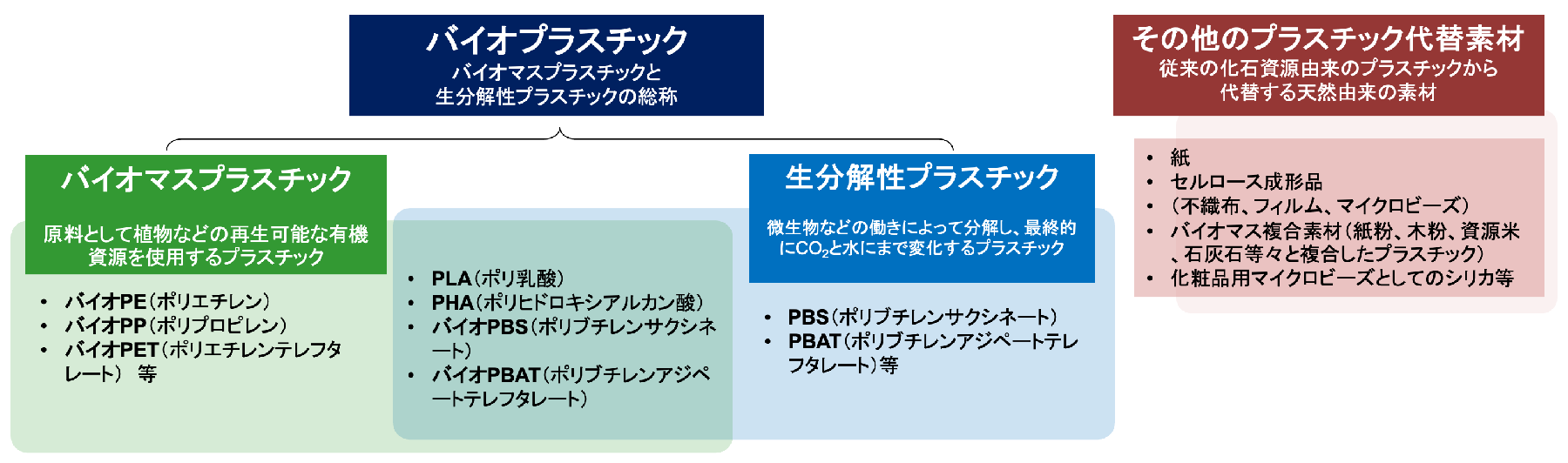

Before diving into Sustimo®, which is manufactured and sold by ELEMUS LLC (“ELEMUS”), let’s review what bioplastics are. “Bioplastics” is an umbrella term for biomass plastics that are derived from renewable organic resources (such as plants) and biodegradable plastics (including those derived from fossil resources). Biomass plastic is considered a carbon-neutral material because it absorbs CO2 from the atmosphere during the plant growth process and does not increase CO2 emissions when incinerated. A well-known example of bio-based biodegradable plastic is polylactic acid (PLA), commonly used in 3D printer filaments. However, PLA requires an industrial composting environment to be fully biodegradable. Biomass plastics also tend to be weaker and more heat-susceptible than conventional petroleum-based plastics, and, because of this, the current trend leans towards the limited use of disposable items and industrial applications of composite materials and other similar materials.

Classification of bioplastics by the Ministry of the Environment (cited by the Environment Agency)

Now, what exactly is Sustimo®? The Tokyo Metropolitan Industrial Technology Research Institute (“TMITRI”) and ELEMUS have been jointly researching and developing this 100% biomass molding material for approximately 20 years. Its main ingredients are fine tree powder (cedar, cypress, etc.) and ki-urushi (urushi sap), a natural plastic component extractable from trees. Heating and mixing these two together produces the powder material Sustimo®. Heating this powder while compressing it in a mold polymerizes the natural plastic component (urushiol) within the urushi, stabilizing it into its molded form with the hardness of a thermoplastic. Based on its material properties, Sustimo® is classified as “plant-derived and non-biodegradable” according to the definition of bioplastics mentioned previously in the article. However, it sets itself apart from conventional bioplastics as it does not use any petroleum-derived raw materials and even emits less CO2 during its manufacturing, highlighting its limitless potential. Sustimo® can currently be used in dishwashers and medical equipment due to its resistance to heat, chemicals, and decay that is on par with ABS resin. The material continues to be developed in hopes of expanding its utility even further.

Sustimo® stands out as a material because cultivating its raw ingredients actually helps the environment, allowing it to be collected indefinitely. Conventional plastics are estimated to generate approximately 5kg of CO2 during the petroleum extraction, distribution, manufacturing, consumption, and disposal stages per kilogram of plastic produced. In contrast, it’s calculated that each kilogram of Sustimo® produced actually reduces one kilogram of CO2, making it a rare material that can reduce CO2 emissions the more it is used. [*1]

ELEMUS reached out to designers to collaborate in order to convey the story behind Sustimo®, including , background, how it can be used, and the vision of the future of the material. ELEMUS commissioned Hidakuma, a company that creates local industries through reforestation and manufacturing in Hida City, as well as FabCafe Nagoya, an innovation lab fostering creative industries and culture with a digital fabrication cafe as its base. They also partnered with two designers: Kaori Akiyama from STUDIO BYCOLOR, a studio known for effectively utilizing the power of color and materials in its work, and Yasuhiro Horiuchi from TRUNK DESIGN Inc., a company that develops brands and products in various regions of Japan through dialogue with local producers and artisans. What kind of synergy will these material manufacturers and designers create after examining and trying to use Sustimo®?

(left) Sustimo® in powder form, (center) ki-urushi, (right) wood powder

As previously stated, the raw material used for Sustimo® is ki-urushi, a traditional material mainly used in East Asia. Ki-urushi is a type of naturally occurring lacquer made by scratching the surface of an urushi tree, and filtering the milky white sap that comes out of it while removing the bark and other debris. Its history is ancient, and it is believed that the urushi tree, which grew wild on the Asian continent, was introduced to Japan during the Jomon period (710-794), before spreading across the Japan [*2]. Urushi crafts (lacquerware) were then refined by the aristocrats of the Heian period (794-1185). However, sources claim that it was not until the 11th century, when the undercoating technique was established, that urushi crafts became widely used as we know it today.

Urushi generally hardens in humid environments through enzymatic activity. Examples of urushi techniques that have developed are maki-e, in which patterns are drawn with urushi and gold powder is adhered to the surface, and raden, in which thinly sliced shells are used to decorate urushi crafts. Urushi eventually came to be polished to a luster, fascinating the world with its beauty. There are also records of Japanese urushi crafts being exported to Portugal, Spain, and other European countries. In the 17th century, the Tokugawa Shogunate held the sole authority to trade lacquerware through the Netherlands, and it was so popular that even Marie Antoinette was an avid collector. The word “japan” in lowercase letters was once so influential that it referred to all Japanese urushi crafts.

Urushi products have long been popular for everything from daily necessities to luxurious ornaments. Unfortunately, their demand has shrunk with the times, replaced by petroleum-derived plastic containers, which are cheaper, easier to process, and able to be mass-produced. Domestic Japanese urushi production is now less than a third of what it was in 1980 according to the Forestry Agency. The project team visited Joboji in Ninohe City, Iwate Prefecture, one of the largest urushi producers in Japan, to directly learn about how Joboji’s urushi industry is supported and how urushi forests are maintained and utilized in collaboration with the forestry association.

Section Chief Hiroshi Taguchi, speaking about the current state of urushi production

The Furusato Cultural Property Forest, an urushi forest managed by Ninohe City in Joboji

According to Hiroshi Taguchi, head of the Urushi Township Development Promotion Section, since the policy shift in 2015 to prioritize domestically produced lacquer for cultural heritage restoration, the production volume of Joboji lacquer has increased. This is mainly due to initiatives such as promoting urushi tree planting on agricultural land and the training of urushi scrapers through the regional development cooperative program. Although cooperation with the Japanese Urushi Tapping Preservation Society and other organizations slightly has increased the domestic self-sufficiency rate of urushi production and the number of people engaged in the urushi business, Taguchi says that the amount produced is still insufficient to restore Japan’s cultural properties[*3].

The municipal urushi forest Furusato Cultural Heritage Forest has about 4,000 urushi trees planted at intervals of 2.5 to 3 meters in an area of around four hectares. According to Taguchi, Urushi trees are not resistant to environmental changes. “Poor land drainage hinders the growth of urushi trees, reducing the urushi it produces depending on its growth.” Though it takes approximately 15 years to harvest urushi from a single tree, one tree only produces about 200 milliliters of urushi (approximately the volume of a milk bottle). When the tree is damaged, the sap will drip out and attempt to repair its own scratches, meaning it is important to monitor the tree’s growth.

Ki-urushi for crafts is produced by a wide range of people, including those who maintain the forests, urushi scrapers who collect the sap, and refiners who filter out tree bark and other waste. At the end of November, the project team visited the site for field research and saw the forest cooperative employees cultivating urushi seedlings. In winter, the weight of the snow can break the urushi seedlings, so they temporarily dig them out and lay them on the ground or put them in greenhouses over winter. “Urushi seeds are collected in autumn and winter. However, roughly just 10-15% of sprouts will germinate with conventional methods. Therefore, it is necessary to refine techniques such as container cultivation and coppicing (regenerating trees from cut stumps) to nurture the sprouts that grow from the base of mature trees,” explained the staff.

These techniques are closely related to the unique urushi production technique koroshi-kaki, in which the sap is removed from a single tree over the course of a year before ultimately cutting the tree down. “We have finally achieved a germination rate of over 90% through our joint research with Tottori University on the previously unexplored topic of urushi germination, allowing the growth of a diverse range of urushi trees. Originally, Aichi Prefecture was one of Japan’s most prominent Mikawa urushi production centers. Right now, we are growing urushi seeds collected in Mikawa from saplings in Okazaki City,” said the staff, surprised by CMO Inaki’s story. It left quite an impression.

Staff cut off excess roots from saplings grown from urushi seeds

Seedlings are sorted by growth

Collected seeds are dried in a net

Through a series of field research trips, the designers were able to gain a lot from their exposure to conventional urushi. “Since it’s the first time we’ve handled this material, both the finished products and the prototypes must speak to the imagination of designers and manufacturers alike and make them wonder just how far they can go with the material. At the same time, we will need sample kits to showcase the physical properties of Sustimo®,” says Horiuchi, who supports traditional craft centers nationwide with the power of creativity, highlighting the importance of post-production.

“There must be more to Sustimo® than just serving as an alternative to urushi and plastic. For example, it would be nice if we could find results from unique things that can only be made using Sustimo®, such as those containing urushi both on the surface and on the inside. Hypothetically, if we could create the luster of urushi by simply polishing the surface without applying urushi after molding, it would open new possibilities for forms different from conventional lacquerware. I believe we must first distance ourselves from the stereotype of how urushi crafts should be and play around with Sustimo®,” says Akiyama, who already had the image of Sustimo® as CG, drawing another connection between the production process and the product itself.

“This is a different perspective from the processing prototypes we’ve experimented with,”said CMO Inaki, both surprised and excited.” He revealed that they ordered new, larger molds, preparing to mass-produce plank and block materials. Furthermore, he mentioned that they have discovered variations in elasticity and color depending on the materials used, prompting them to decide to experiment with mixing Sustimo® with wood powder from various sources such as bamboo and broad-leaved trees right there on the spot.

Both designers, who have extensive experience exhibiting overseas, emphasized the importance of “updating research and making the process available to the public” as the premise for exploring the material’s limitless possibilities. To this end, they’ve created flagship products by designing appropriate materials that are usable by manufacturers and designers alike, while showcasing the allure of the material through development stories and sample kits. They named this design-driven initiative “Stustimo Lab” and stated their intention to proceed with its preliminary development by March 2024.

Members participate in a discussion in Morioka City

“That gave me a lot of homework for the year,” said CMO Inaki after two days of field research in Iwate Prefecture while sipping Morioka cup noodles with a content expression.

The next report will cover the processing experiments and other activities that took place in Hida City just two weeks after the Iwate trip. We look forward to showcasing the new possibilities discovered after examining and tinkering with materials together with designers.

ELEMUS is currently making (paid) material samples. To receive a sample, please register your email address using the form linked below. We will notify you as soon as preparations are complete, around the spring of 2024.

Click here to sign up for the waiting list to receive SUSTIMO® samples.

*1: As the amount of CO2 absorption by urushi trees is still being measured, the calculation is based off of an estimate.

*2: According to the National Museum of Ethnology’s research study, “Origin of Urushi

(Toxicodendron vernicifluum) in the Neolithic Jomon Period of Japan,” the presence of urushi has been found in Japan from Jomon Period fossils and from the Torihama shell mound site in Fukui Prefecture.

*3: Although urushi crafts are produced in various regions from Okinawa to Aomori, a survey by the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries shows that Iwate Prefecture accounts for about 75% of all urushi production. However, Japan’s self-sufficiency rate is only about 5%, relying mostly on imports from China. The Urushi Township Development Promotion Division is making various efforts to pass on the local culture to future generations.

-

Kakeru Asano

Design Researcher

Kakeru Asano was born in Hyogo, Japan, in 1987, and grew up in Nagoya. In 2014, he completed his graduate studies in Design Management Engineering at the Kyoto Institute of Technology and began working as a design researcher based in Nagoya.

He is driven by the philosophy of “realizing social inclusion through design research” and engages in a broad range of integrated design activities, from research design to brand/product development and management strategy planning.

Under the slogan “design research methods that pave the way to unknown challenges and possibilities,” he makes integrated proposals through contextual understanding and narrative construction (vision).

Website: https://kakeruasano.com

Kakeru Asano was born in Hyogo, Japan, in 1987, and grew up in Nagoya. In 2014, he completed his graduate studies in Design Management Engineering at the Kyoto Institute of Technology and began working as a design researcher based in Nagoya.

He is driven by the philosophy of “realizing social inclusion through design research” and engages in a broad range of integrated design activities, from research design to brand/product development and management strategy planning.

Under the slogan “design research methods that pave the way to unknown challenges and possibilities,” he makes integrated proposals through contextual understanding and narrative construction (vision).

Website: https://kakeruasano.com