Event report

June 9, 2022

David Willoughby

Freelance Writer

Recent hype around smart cities has tended to ignore an inconvenient truth: most people actually quite like the slightly disordered and endlessly varied tenor of urban life. The social fabric, it turns out, is infinitely complex in ways that a top-down, technology-led approach doesn’t even begin to capture.

What’s more, despite the claims made for it, technology itself doesn’t deliver social change. It only acts as an enabler for people, usually in groups, to bring about that change themselves. Therein lies the concept of a smart community.

Smart communities mark a shift from the Internet of Things towards something that might be described as the Internet of People. They also bring us back to the fundamentals of human social behaviour. What motivates people to join groups, volunteer their time, or support a cause? And how can we leverage the power of human networks to make our communities better informed, more sustainable, and ultimately more resilient?

This two-day talk event and mini jam was hosted by FabCafe Global and Atelier Future at National Cheng Kung University (NCKU) in Taiwan. Co-created with Loftwork, the event is part of an anticipated series of workshops in which students will address global social challenges.

Densely-populated, disaster-prone Taiwan is a beacon of digital democracy and social participation across all age groups. During this event, NCKU students joined counterparts in Japan and other countries to hear from leading community-builders and share ideas on how to address social challenges with a community-led approach. We’ll hear from the students in Part 2 of this report, but first let’s meet the guest speakers.

Keiko Ono is a cofounder of Social Innovation Japan, a platform for bringing together companies, governments and social changemakers to tackle real-world problems. With her background in community organising, strategic consulting and her day job at Google, Keiko spends a lot of time thinking about how communities scale and manage their resources. She sees community as a meta product of the digital products we use in our lives:

With technology, we’ve seen that you can grow a community from zero to ten thousand. You can have one employee organise something with more leverage than the entire company’s budget online. I think it’s important to take this into account, because we’re not used to that speed.

She shares some best practice for bootstrapping a community, drawing analogies to the product development process: create feedback loops to collect data from members, nurture champions who believe in your cause, create a signature identity for the group, and do regular capacity checks to ensure the community can continue to function and manage enquiries as it scales.

Keiko wants us to view technology as an enabler of community, but not its ultimate purpose. A smart community can alter the power dynamics between individuals and groups and create a more equitable society. It can do this by fostering agency, facilitating learning, and providing shared experiences. In her words, “smart” communities scale the small things that influence power.

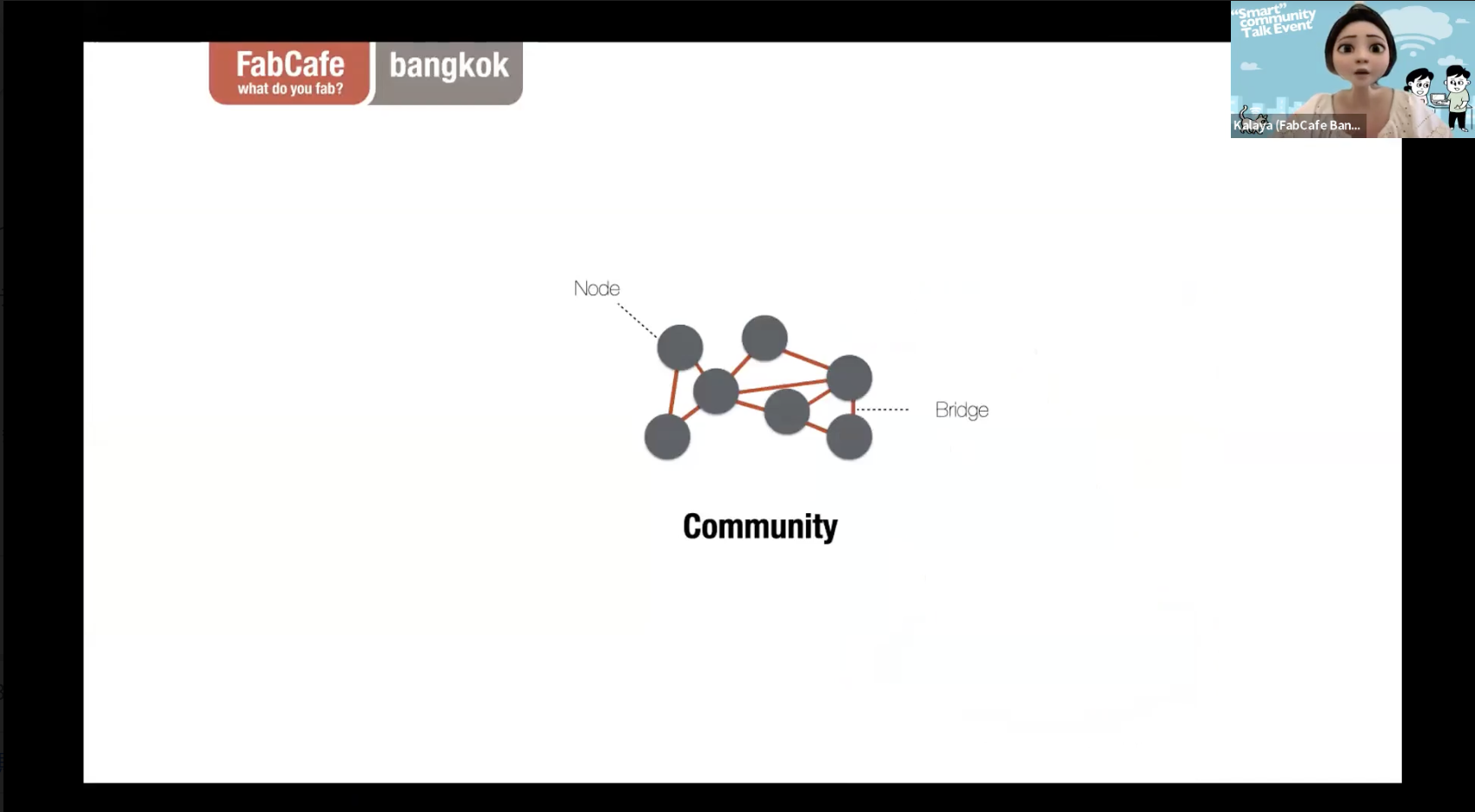

Kalaya Kovidvisith is a cofounder of FabCafe Bangkok and Managing Director of FABLAB Thailand, where she plays a pivotal role as a community builder for Thai creators and designers. Building on her postgrad studies in design and computation at MIT, Kalaya explains how she applies the concepts of systems, nodes and bridges when strategising community formation.

A system might reflect a community’s purpose or the benefits members gain by belonging. Kalaya’s own community work runs on a system that involves turning local creators into global creators, which she does by organising meetups, creating spaces for collaboration, and leveraging the reach of the FabCafe Global network and the YouFab platform.

Kalaya suggests one growth hack for communities is to identify nodes, or well-connected individuals. The concept might be familiar to some from NodeXL, a software tool that maps social influence by visualising Twitter conversations. Potential nodes might be hub influencers for the immediate community or bridge influencers to related groups and fields.

The different ties between people or groups can be classified as bridges. Kalaya would like us to consider community as one type of bridge among many, each with optimal ways to pursue co-creation:

- Crowds respond best to open events that anyone can join, such as challenges.

- Communities are people with a shared interest but no formal ties – they need initiatives such as hackathons to bring them together.

- Clubs have a formal structure and often a source of funding – maker clubs being one example common to FabCafes.

- Coalitions are ties between groups with a common objective, such as the city-level innovation projects Kalaya and her team have been organising in Thailand.

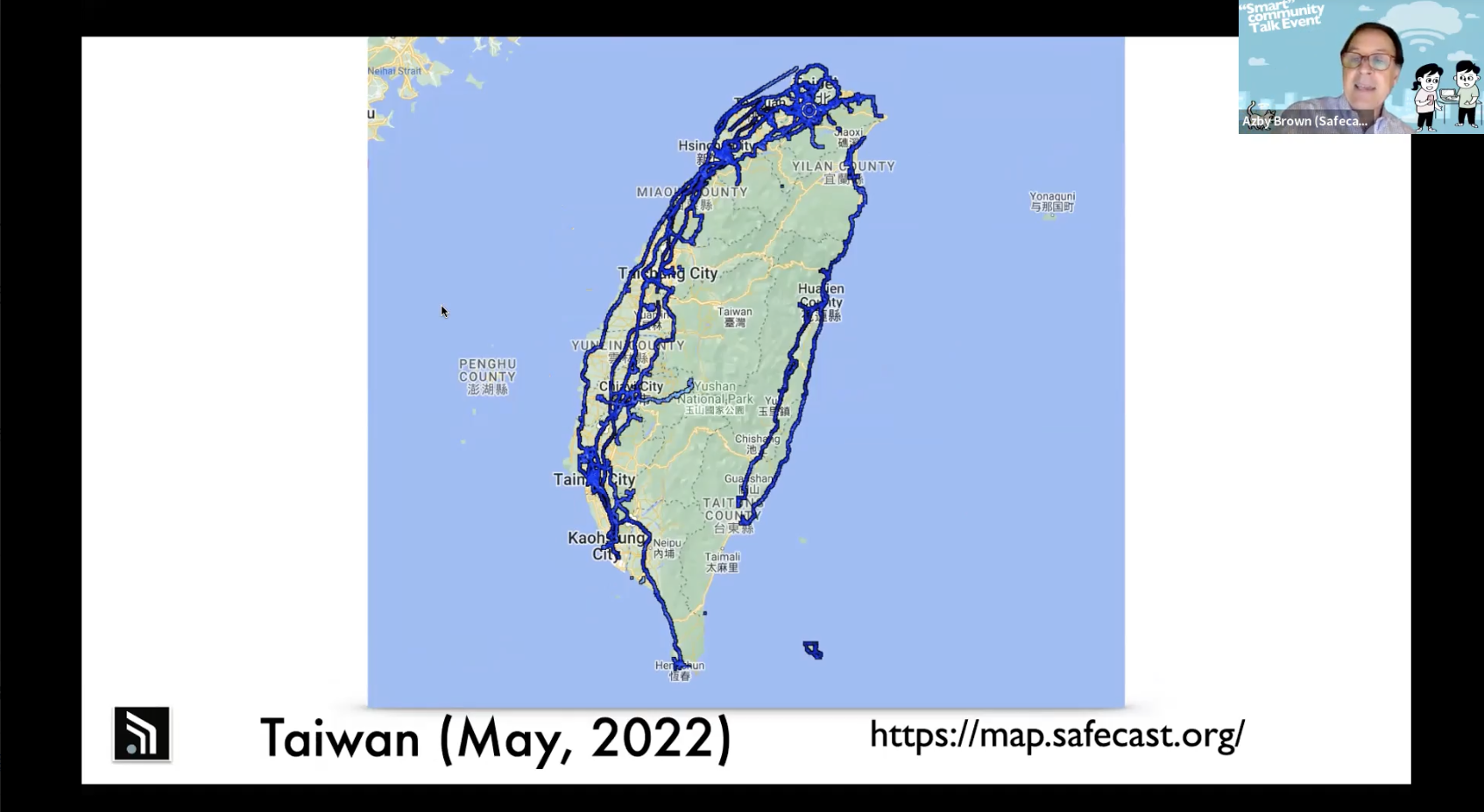

Azby Brown, author of several books on design and sustainability, is a lead researcher for citizen science NPO Safecast. Formed in the immediate aftermath of the 3.11 disaster in Japan, when public trust in official information sources collapsed, Safecast provides DIY sensors for radiation monitoring and makes all the data open-source.

Safecast now provides access to 160 million data points collected from over 120 countries. It continues to maintain 17 real-time sensors around the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant, and has expanded to offer air-quality sensors providing valuable real-time data during global environmental events such as forest fires.

The entire organisation is volunteer-based. We learn how a single community member has mapped an entire city in one year by varying their daily routine. Similar to Wikipedia, Safecast seems to have cracked the code of providing a meaningful experience to community members in order to harness their contribution at scale. Azby admits this wasn’t obvious at the beginning:

Initially, everyone involved in the project thought that the hardware, the software and the database would be the most challenging part, but of course it was building and maintaining the community. This has been a great learning experience for all of us. We have a very broad spectrum of stakeholders, people from all walks of life. That communication and support has been the most important thing.

Tokyo Hacker Space was one of the earliest physical manifestations of the Safecast community back in 2011. This was followed by education programs and workshops for adults and schoolchildren across Japan and several European countries.

Azby points out that a community-centric approach has one critical advantage over a device-centric one. The Internet of (No)things is how he describes the likelihood that a product or platform will one day face the loss of its infrastructure or other critical support. A community that’s non-hierarchical, loosely networked, and open to all has an in-built resilience that few technologies can match.

Chris ‘Akiba’ Wang and Jacinta Plucinski are cofounders of FreakLabs, which develops Arduino-based hardware for wildlife research, environmental conservation and basic infrastructure in rural and remote areas. They joined this talk event to share their experiences of working with communities of people who are far from digitally native.

One of their projects called Hacker Farm began life in 2012 in a rural area of Japan, where many rice farmers are now in their 80s. Growing rice is a communal activity and highly dependent on water. Monitoring water levels in rice paddies is a daily necessity, but the remoteness of the paddies and the age of the farmers make this physically difficult. FreakLabs helped set up remote monitoring equipment that sends regular updates via email – or telephone for those who prefer.

Akiba and Jacinda define a community as a group of people with a common interest, or working together towards a common goal, just like these rice farmers. Other examples include groups which manage a common resource, such as soil or livestock. However, when it comes to “smart” communities, they believe technology is not the defining factor here:

A smart community is one that:

- has diverse skillsets and experiences

- can communicate effectively

- is mindful of the impact of its actions on those not participating in the community as it achieves its aims in the best way.

A technology-driven solution might be counterproductive in areas where it can’t be supported or the technical proficiency of the community members is low. Any technology needs to be appropriate and may already exist at the local level. It might not even look like technology, at least from the perspective of the university-age participants in this workshop.

Akiba and Jacinda also want students to consider the scope of technology in any project. Sensors might be useful as a monitoring tool to help prevent wildlife poaching, but will the project ultimately depend on human intervention, for example by deploying rangers to the location? The need to factor in the limitations of technology and the role of human actors is their message for the students joining today.

Next, the speakers got into a lively crosstalk about some of the more practical issues around community-building, such as managing egos and the importance of acknowledging all members’ efforts. They also brought up some further discussion points, such as the question of transparency around whether a community has future commercial aims or will be strictly nonprofit.

That discussion, together with all presentations from today’s talk event, can be viewed in full below.

NCKU students and other participants also had a chance to meet the speakers in smaller breakout rooms and ask questions of their own. On Day 2, they’ll be back for a mini jam in which today’s learnings will provide the basis for some community-driven thinking around the social issues they care about most. Find out what happened next in Part 2 of the report.

-

David Willoughby

Freelance Writer

David thinks and writes about sustainability, technology and culture, and has reported on many of our hackathons, talks and other events. He also works with Japanese companies to help tell their stories to the world.

David thinks and writes about sustainability, technology and culture, and has reported on many of our hackathons, talks and other events. He also works with Japanese companies to help tell their stories to the world.