Column

January 28, 2026

FabCafe Global Editorial Team

BioClub Tokyo, an open community of biology enthusiasts, hosted the seventh annual Tokyo Art & Science Residency in partnership with the Finnish Institute in Japan. Since 2018, the residency has been organized by the Bioart Society, a Finnish organization dedicated to facilitating activities around art and the natural sciences, especially biology and the life sciences.

Past residents include Johanna Rotko ‘20 (BIO ART LAB, YEASTOGRAMS-Laboratory) and multidisciplinary urban artist Antti Tenetz ‘23. Residents are selected for both the artistic and conceptual richness of their practice as well as the thoroughness of their plan for this unique Japan-based experience. They are encouraged to travel within Japan to supplement their work, and many residents create deep, lasting connections with both BioClub members as well as external collaborators. In fact, Aaro Murphy ‘22 returned to Japan as a resident of the Tokyo Arts and Space Exchange, or TOKAS, in 2024.

For the 2025 edition of the residency, the selection committee — which comprised members of BioClub Tokyo, the Bioart Society, and the Finnish Institute in Japan — interviewed four finalists before choosing Santtu Laine for the opportunity.

Santtu’s goal for the four-week residency program was to continue his ongoing research into seaweed-based bioplastics. As seaweed has been part of Japanese culture and cuisine for over a thousand years, the residency seemed a perfect place for Santtu’s practice. In the lab, Santtu hoped to create new bioplastic samples and use marine bacteria to etch patterns into their surfaces. More broadly, he planned to visit a factory to learn more about seaweed uses and processing, as well as the relationship between these marine plants and the people who rely on them.

Kaisou and kombu and kanten, oh my

Most people are aware of seaweed and kelp used to wrap sushi rolls (nori) or boiled to make soup broth (kombu — the popular drink kombucha is, in fact, unrelated and contains no seaweed). Agar, a seaweed derived product, is a familiar sight in biolabs around the world, where it serves as a key component in plates that hold bacterial or fungal cultures. A lesser known fact about agar: it’s been a common ingredient in Japanese foods for centuries.

For hundreds of years, agar (kanten in Japanese) has been used in many Japanese foods and confectionaries. It is essentially a vegetable gelatin, forming the base for jellies and puddings, often flavored with syrups or filled with fruit or sweetened red beans. Where Japan’s kanten market once thrived, climate change has forced many to shutter, leaving just a handful of producers left in Japan.

While warming seas force kanten producers out of business, the production and disposal of oil-based plastics continue to harm our oceans. Seaweed-based plastics and packaging have been praised for their potential to create alternative, more eco-friendly packaging for over a decade — so where are they? These tensions between society and the environment are a driving force in Santtu’s investigations into sustainable biomaterials in Japan and beyond.

-

Santtu Laine

Santtu Laine is a Finnish multidisciplinary artist based in Helsinki, Finland. His practice spans installation, sculpture, photography, moving image, and sound, with a strong focus on exploring alternative and sustainable methods of art-making. He frequently works with bioplastics derived from seaweed, emphasizing the creative potential of renewable, non-hydrocarbon materials.

In addition to his artistic practice, Laine teaches a hands-on laboratory and workshop course at the sculpture department of the University of the Arts Helsinki, combining practical bioplastic-making with material science and sustainable art practices.

Santtu Laine is a Finnish multidisciplinary artist based in Helsinki, Finland. His practice spans installation, sculpture, photography, moving image, and sound, with a strong focus on exploring alternative and sustainable methods of art-making. He frequently works with bioplastics derived from seaweed, emphasizing the creative potential of renewable, non-hydrocarbon materials.

In addition to his artistic practice, Laine teaches a hands-on laboratory and workshop course at the sculpture department of the University of the Arts Helsinki, combining practical bioplastic-making with material science and sustainable art practices.

For his first introduction to the community, Santtu gave a talk at one of BioClub’s weekly Tuesday meetings on November 25, 2025.

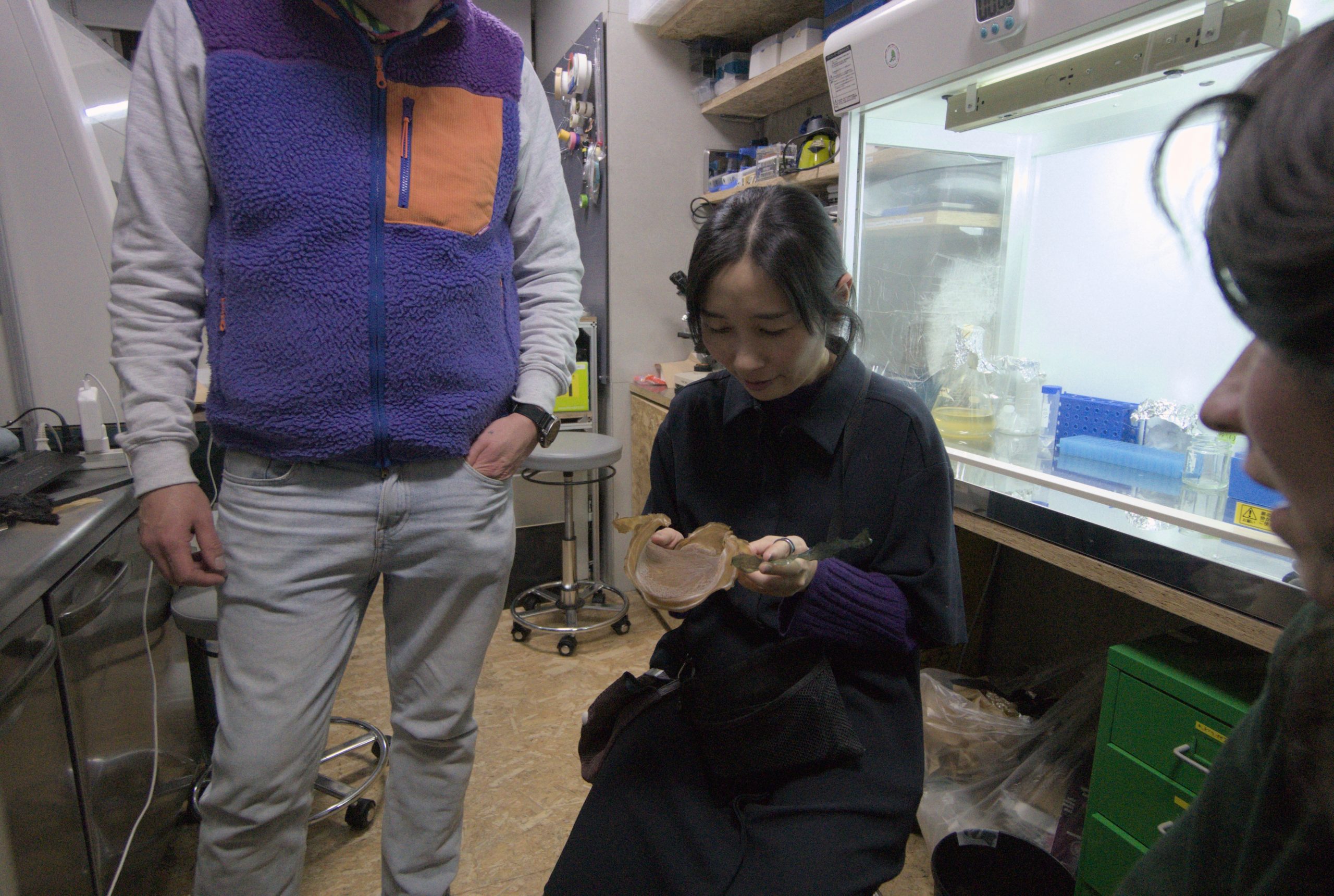

In addition to introducing his practice and body of work, Santtu brought several samples of seaweed and bioplastics for attendees, to see, touch, and even smell. Santtu’s practice explores the relationship between the raw materials and the finished object, meaning his bioplastic recipes require minimal processing and additional ingredients. To make glossy, pliable bioplastics, he adds glycerin to either agar or a piece of seaweed. However, some varieties of seaweed can hold together without additional materials; these samples still smelled strongly of the ocean. One attendee commented that the samples were beautiful, and also made them hungry for seaweed soup.

The very next day, Santtu was in the lab cooking up bioplastics. At his home studio in Finland, he has access to a large heating device to expedite the drying process for his samples; in the smaller confines of the BioClub lab, he had to get creative, adapting his workflow to limited counter space.

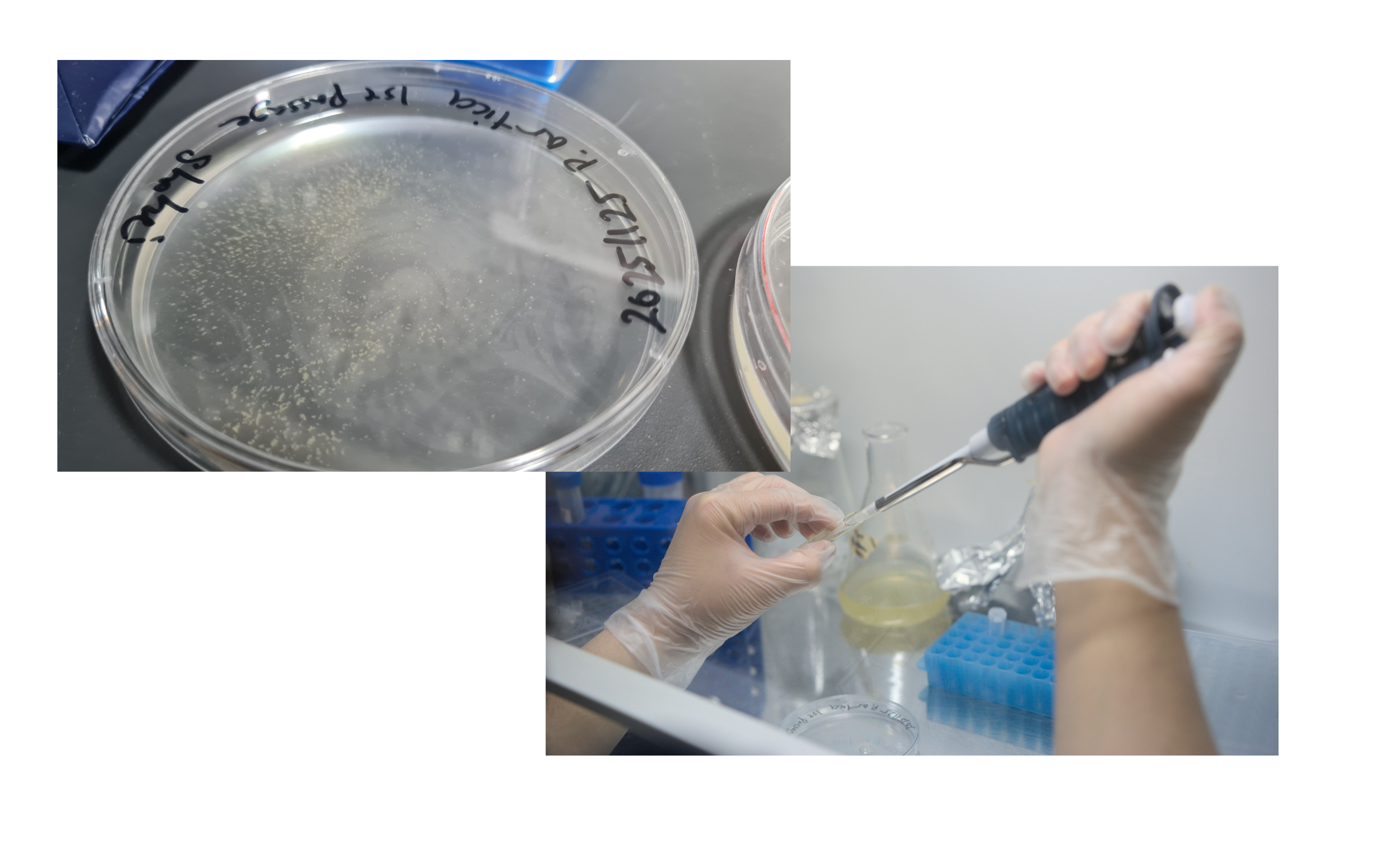

From day one, Santtu worked closely with BioClub volunteer Shohei Asami to learn about aseptic laboratory techniques and how to culture his marine bacteria. As a community-driven organization, BioClub sees many members with laboratory knowhow work alongside new members to teach them about fundamental lab skills. This community spirit extends to residents as well, with community members often offering to help or mentor, or even just providing lists of local stores or restaurants.

In conjunction with his experiments in bio-etching, Santtu was also able to build on the work of last year’s resident, dye and textile researcher Lau Kaker. Last year, Lau cultivated a traditional Japanese indigo dyeing vat, which was still viable during Santtu’s residency. After getting the OK from Lau, Santtu dyed bioplastic samples in indigo. Inspired by the results, he continued his dyeing experiments with kakishibu, another traditional Japanese dye made from fermented persimmons.

On the final day of the residency, Santtu hosted an open lab, where members could see the output of his residency and have in-depth discussions about his time in Japan. In the close quarters of the lab, people handed around bioplastic samples, admiring the blue and red hues of indigo and kakishibu filtering the fluorescent light. Santtu recounted a research trip he took the previous week to Gifu Prefecture, where he visited one of Japan’s few remaining kanten factories. While describing his experience, he showed photos he took of old women checking kanten strips for imperfections before being sent for packaging and of a courtyard full of seaweed drying in the cold, dry air.

One attendee who had attended the introductory talk inquired about the bio-etching experiments. In the end, according to Santtu, the bacteria worked on scales of time and space too small and slow for the scope of the residency. The designs they ate into the bioplastics were simply too fine for the human eye, and making them visible would take longer than a month.

However, said Santtu, perking up, his residency had opened his eyes to the potential of using indigo in his practice. Not only did indigo physically work with the bioplastic, but the crossover between the twin Japanese heritages of indigo and seaweed held potential for new artistic exploration. In fact, he had bought the raw materials for an indigo vat and would start one at his Finland studio.

It was, as always, bittersweet to bid Santtu farewell at the conclusion of the residency. Nevertheless, it was with the promise of new explorations for both Santtu and for BioClub: Santtu would be bringing a bit of Japan back to Finland to bring something new to his practice, and BioClub is looking forward to the 2026 residency. While looking forward to next year, the community is also buoyed by the synergies Santtu found with a previous resident’s practice — maybe this year’s resident will find inspiration in seaweed?

The open call for the 2026 residency is open through January 31, 2026. For more details and application information, check out the Bioart Society’s official website.

-

FabCafe Global Editorial Team

This articles is edited by FabCafe Global.

Please feel free to share your thoughts and opinions on this article with us.

→ Contact usThis articles is edited by FabCafe Global.

Please feel free to share your thoughts and opinions on this article with us.

→ Contact us