Interview

June 8, 2023

Sarah Ho

FabCafe Kyoto

In the second volume of SPCS Talks, SPCS interviews Julia Moser, textile and fashion designer and YouFab 2021 finalist for her project Growing Patterns, Living Pigments. Her work was also exhibited in FabCafe Kyoto and FabCafe Tokyo from March to April.

In this interview, we explore Julia’s motivations behind bacterial dyeing and discuss the implications and possibilities that her bacteria dyes open up for the fashion and manufacturing industry.

Cover Photo: Julia Moser exhibiting at Ars Electronica. Photo credits: Florian Voggeneder

It started with photos of polluted waterways, rivers in China, India and Mexico dyed toxic by textile factories that conveniently dumped their untreated wastewater into the nearby rivers. As a fashion and textile designer, Moser was confronted with the reality that her choices of materials and production methods had a very real and visible impact on the environment.

But as she delved in deeper, she also realised that sometimes the answer lies close to the problem. In her research, Moser had come across images of water bodies in unexpected hues. This time, the colours were not a byproduct of manufacturing, but a result of algae and bacterial growth in the water. This triggered the question of whether it would be possible to dye textiles with these naturally coloured waters instead of dyeing waters with unnaturally coloured textiles.

Lake Hillier, a naturally pink salt lake off the coast of western Australia.

Image credit: Wikimedia Commons (CC BY-SA 4.0)

With this hypothesis, Moser started to work with the strain Janithobacterium Lividum in a laboratory. However, she is quick to mention that she is not the first to work with this strain. It was first discovered in 1990 by a group of Japanese researchers who found out that it stained the silk nets of Japanese fishermen bluish-purple. In addition, there are a number of start-ups working with bacteria to turn them into dyes.

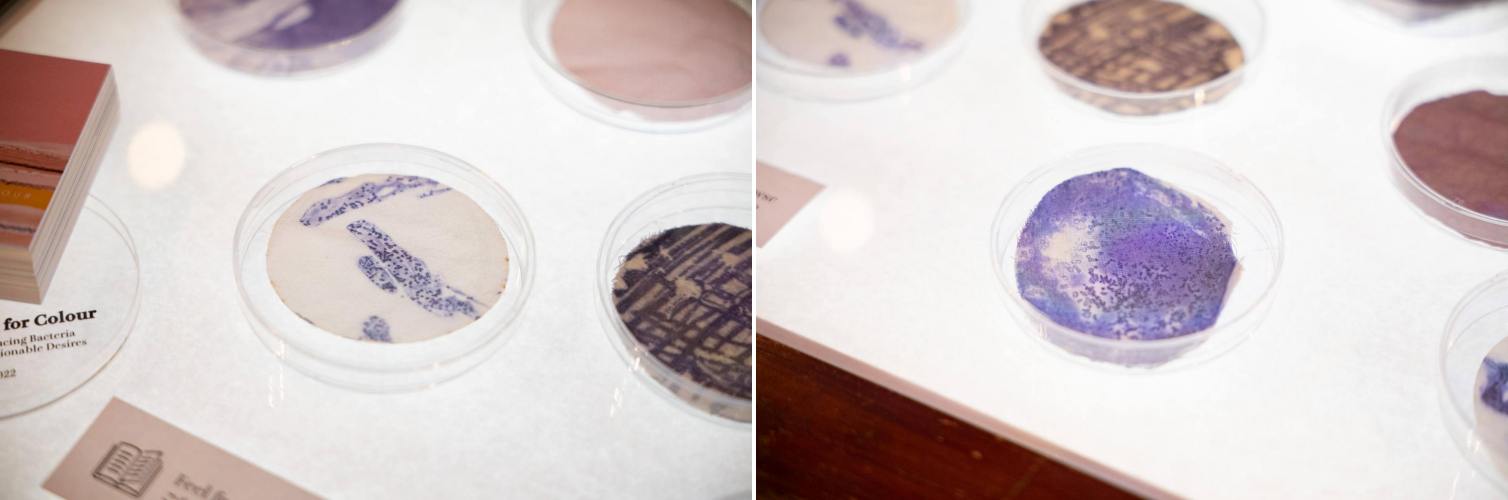

Bacteria growth on fabric samples on exhibit in FabCafe. Image credits: FabCafe Kyoto

According to Moser, the great thing about using bacteria is that it does not need a lot of land, water and time, as compared to growing and using natural dyes. As for synthetic dyes, harmful chemicals used in the dyes compounded with a lack of regulation or enforcement of safe treatment often leads to pollution of waterways (1) or toxic chemicals left on fabrics. (2) In comparison to synthetic dyes, bacterial dyeing doesn’t use any harmful chemicals, leading to health advantages both in production and while wearing the final product.

Julia Moser shares with us the advantages of dyeing with bacteria. Image credits: FabCafe, Julia Moser

Furthermore the bacteria dye works on synthetic fibers as well. While many natural dyes cannot fix onto synthetic fabrics, certain strains of the pigment producing bacteria have been found to dye synthetic fibers too.

However, when she first started, the existing literature did not contain much research on pattern designs with bacteria and that was where she sought to produce intentional patterns with the bacteria dye. Teaming up with the Vienna Textile Lab, she utilized a range of techniques from traditional Jacquard weaving to new methods such as UV printing and laser engraving to produce a variety of stunning results.

Samples of different pattern-making techniques in contrast to their undyed counterparts. Photo credits: FabCafe Kyoto

Julia in front of her bacteria dyed samples, and textile woven from bacteria dyed thread. Photo credits: Julia Moser

The following year, she continued her research with bacteria, this time looking for different colours from nature around her. In 2021, Moser and her research team from the Johannes Kepler University (JKU) collected bacteria from around JKU where the Ars Electronica Festival took place. After cultivating the foraged bacteria, they then exhibited it at the exact same spots they were collected from. A number of these strains were found to also dye textiles, which were then exhibited in the Ars Electronica Festival 2021.

Fabric samples dyed different colors with different bacteria strains. Photo credits: FabCafe Kyoto

Moser is positive about the adoption of bacteria in the textile industry despite the challenges.

I think actually the industries are going to work with bacteria as pigments and dyes but more in this direction of really using the pigments from the bacteria and maybe also combined with synthetic biology and probably not in the way I did it.

Firstly, Moser comments, using the living organisms to dye fabrics as she did would result in unexpected outcomes, and in the manufacturing industry, replication is important, such instability would be hard to tolerate.

The next issue is that working with living organisms is more complicated than traditional ways of dying textiles. It would require more trained workers that have the necessary expertise. Another issue that industries would face is the limitations in the colour palette.

Fortunately, there are companies working through synthetic biology and other means to extract just the pigment from bacteria. They are capable of producing a broad color palette through modifying bacteria. A few of these companies are Colorifix, Pili and the Vienna Textile Lab.

What exactly are the methods Moser employs that she feels are unsuitable for commercial application? Her recent research relies on letting the bacteria grow freely, and interpreting their growth patterns. These are ongoing conversations with non-human organisms that companies would find hard to follow, it is often easier to view such non-human organisms as resources instead of collaborators.

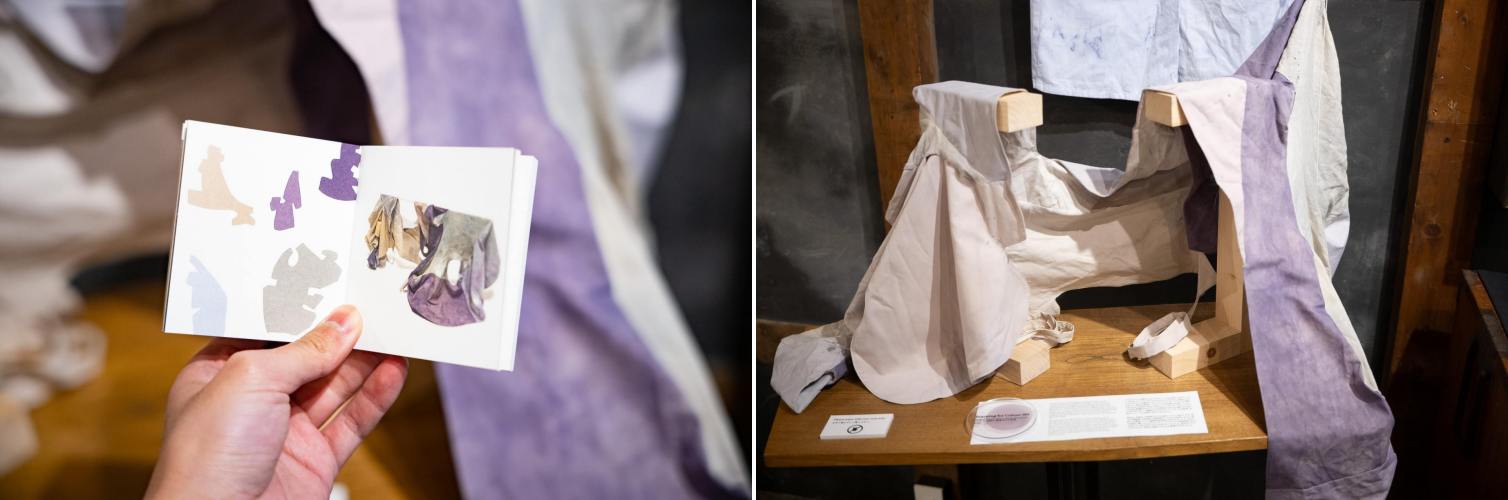

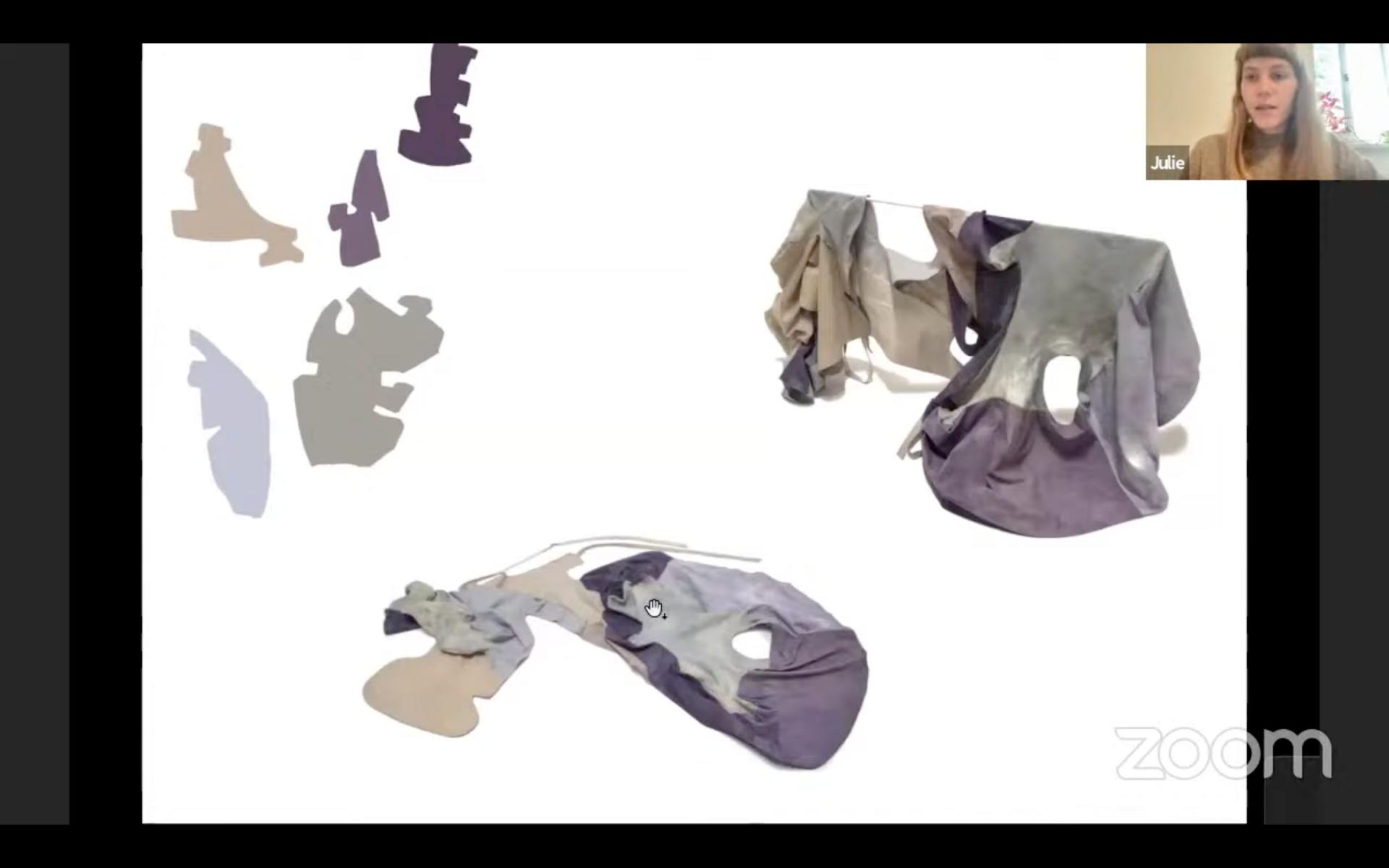

One such work of Moser’s that involved reading the shape of bacteria growth developed into a jacket. She allowed bacteria to grow freely on fabric to then use the shapes they drew as cutting pattern shapes for fashioning a jacket.

Left: Shapes of bacteria growth images in Yearning For Colour . Right: Jacket fashioned from bacteria growth shapes.

Photo credits: FabCafe Kyoto

In her experimentation, she found that the bacteria might produce different results despite seemingly consistent input. This eventually led her to co-create a language with the bacteria.

I just was thinking about the process itself when I was working with the bacteria in the lab and many times when I was working with them it was like under seemingly the same circumstances they created different shapes and they reacted in a different way.

Sometimes they left me with a lot of questions and I was wondering, what do they want to tell me? Why are they reacting like this although I did exactly the same thing as the last time? It was very interesting to work with them because it was always full of surprises.

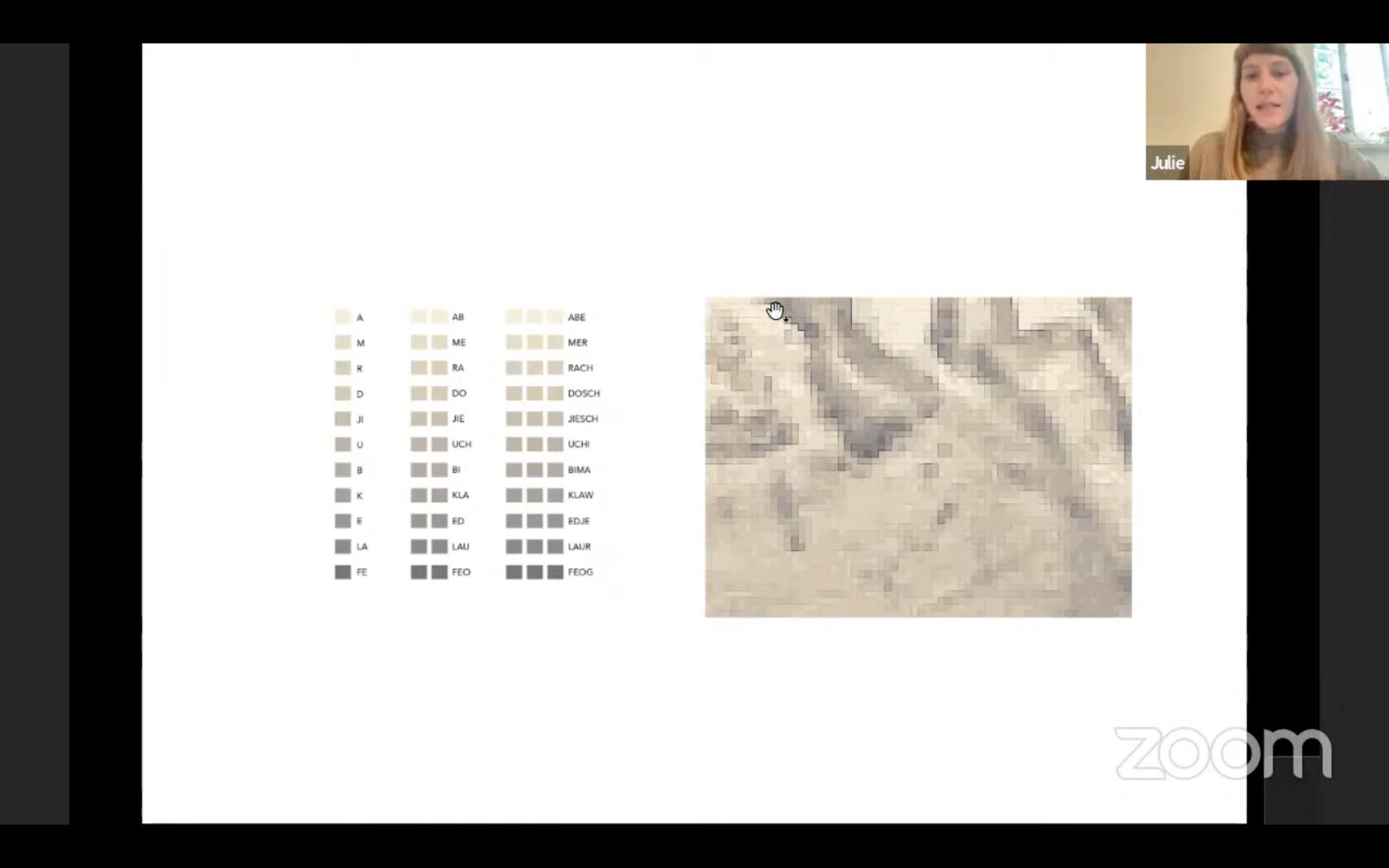

The shape of growth and hues the bacteria produced became the basis of a new language. By reducing the growth patterns into pixels, she could assign each individually hued pixel a certain alphabet. When strung together in an order, the pixels produced something that sounded language-like. In one work, this language soundscape featured in a performance with a dancer and a musician wearing the bacteria-dyed garments, surrounded by spoken language and music as a translation of the bacterial growth. Another version of this language was depicted in an installation where Moser passed dyed fabric samples under a webcam that then read out the words created by the pixelated language.

Moser explaining the process of pixelating and creating the language with bacteria

Photo credits: FabCafe, Julia Moser

Below, a video teaser of the performance that featured the language soundscape.

The use of pixelated growth patterns extended into music and computer-programmable knitting too. Instead of assigning an alphabet to each pixel, Moser swapped each one out for a musical note, and thus created a music sheet for a handpan.

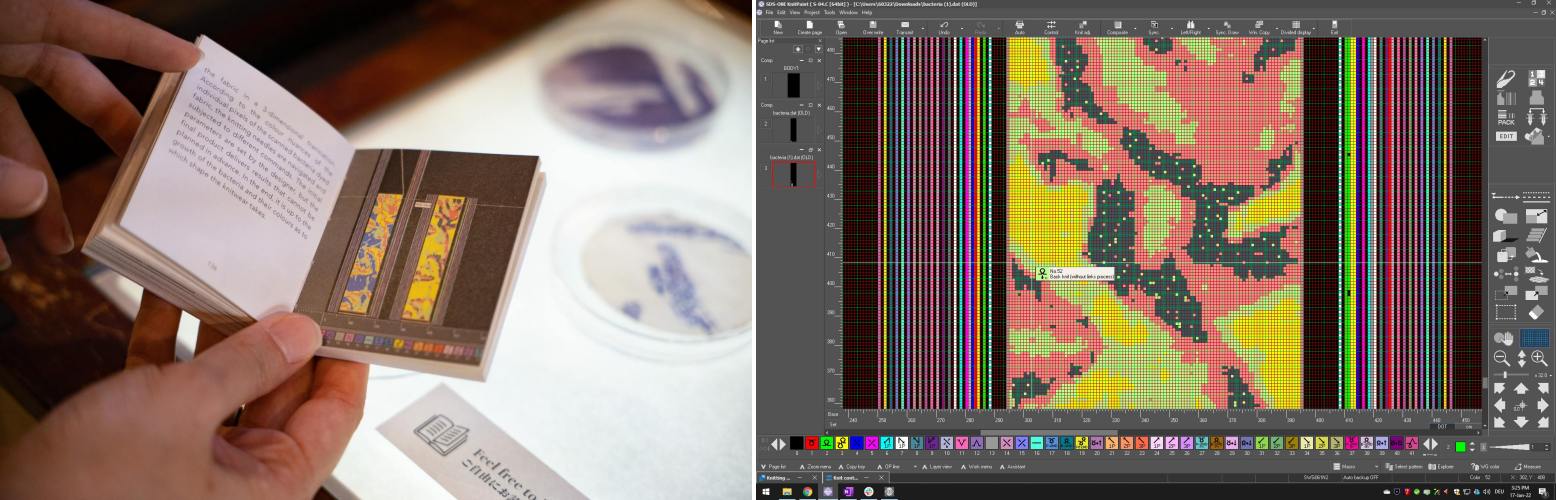

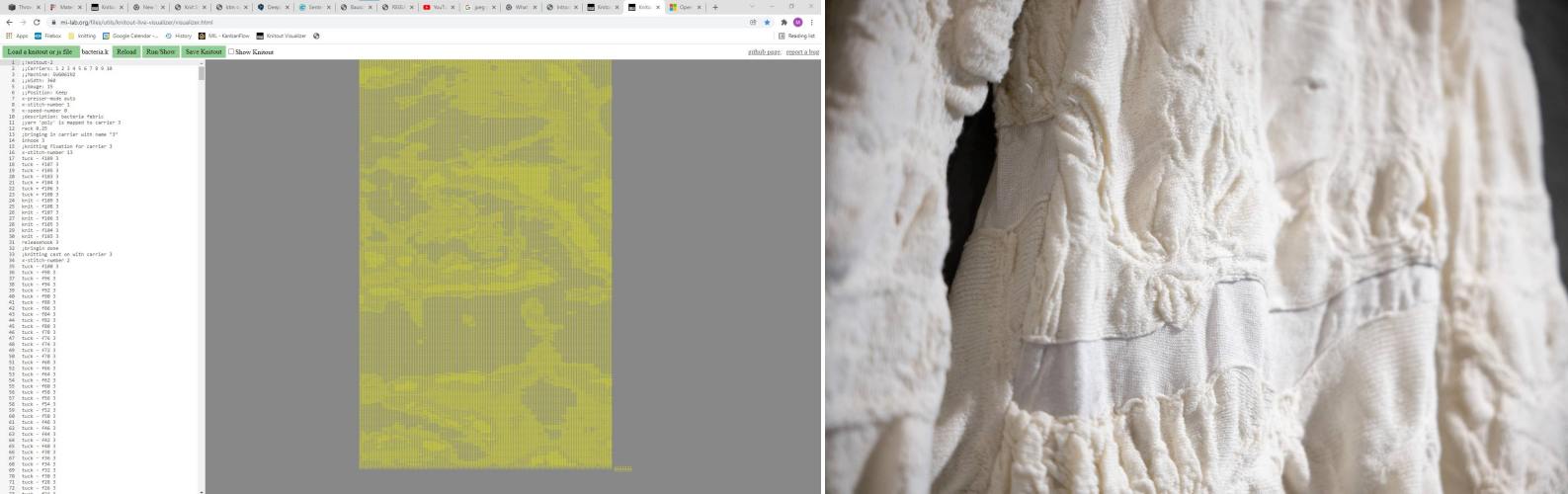

In another work, the pixels were translated into knitting commands for a sweater. A knitting program is depicted by multiple pixels, with each pixel determining the stitch used at that point. After translating a knitting pattern out of scanned bacteria growth patterns. Moser proceeded to knit a sweater out of white wool. This turned the colours of bacteria into the uncoloured texture of the sweater.

Screenshots of knitting software Moser used to translate the bacteria growth patterns into knitting data.

Left photo credits: FabCafe Kyoto, Right image credits: Julia Moser

Left: Bacteria growth translated into knitting patterns Right: Sweater textured with bacteria growth patterns..

Left Image credits: Julia Moser, Right photo credits: FabCafe Kyoto

For instance, when co-creating the language with the bacteria, the experiments and growth of bacteria were carried out under strict aseptic conditions, but the assignment of sounds, alphabets or knitting commands to each pixel was subject to Moser’s own judgment and what she felt the bacteria was trying to say. Such is the tension between the rigorous scientific process she adopts together with the emotional, intuitive approach to analyzing or interpreting the results.

Again, in her work on the jacket pieced together from shapes drawn by bacteria, she marries the seemingly opposing concepts of sterile cleanliness with bacteria and uninhibited growth. The jacket was created from discarded fabric from hospitals, textiles that were expressly kept away from bacteria. In a twist of fate, they are intentionally used by Moser to grow bacteria for a healthier future..

Julia Moser introduces the jacket made from shapes ‘drawn’ by bacteria growth.

Image credits: FabCafe, Julia Moser

It was also a very interesting juxtaposition that I could create in the storyline because the hospital textiles haven’t seen bacteria for their whole lifespan in the hospitals. In the hospitals, they try to get rid of the bacteria actually and so they were held in sterile conditions. But now after they have been discarded, they get in contact with the bacteria but still to create more health for the environment.

It comes full circle, the sterile environment the hospital fabrics were kept in was to maintain health and hygiene. Now the use of bacteria to dye it is an effort to restore health to the planet and the wearer by using a sustainable, non-toxic dye.

One might question the durability of dye using bacteria. Moser answers that it all depends on the strain. Each strain of bacteria is unique, some might fade faster, some would last longer. They are more comparable to natural dyes.

But just as natural dyes fade, another way to look at it is to think of it as a new chance to refresh your clothing in a new colour when it fades. It begs the question of consumers, are we willing to take on the challenge to accept that our clothes change and work with that instead of tossing them out the moment they start to change?

The adoption of bacteria as a pigment for dyeing textiles may be new and still incompatible with our current manufacturing processes and consumption habits. However the discovery and ongoing research into this novel solution for the long-standing issue of pollution in the textile industry still astounds us with its elegant simplicity. Perhaps sometimes, solutions are in plain sight, we just need to reframe them to make them visible.

References

- The Issues: Chemicals, Common Objective

- Toxic Threads – The Big Fashion Stitch-Up, Greenpeace

-

Julia Moser

Textile & Fashion designer / Founder of Growing Patterns Living Pigments

Julia Moser sees her mission in re-thinking fashion and textile design practices and production processes towards a more sustainable and healthier future. Following the fact that nature knows how to produce colours without chemicals and harmful ingredients, she founded “Growing Patterns Living Pigments” and started to co-creating with pigment producing bacteria for dyeing textiles and involving them in the design process as well. With a focus on material innovation and bio design, she uses new technologies to find alternative ways of thinking design and design processes. Always remembering the indigenous tribe of the Kogi saying “You’re meant to work with technology, but if you do so, use technology that works with and not against nature”. Holding two Master degrees in textile.art.design and Fashion&Technology from the University of Art and Design Linz she’s currently working as a University Assistant at the Crafting Futures Lab. There she’s working on her PhD and guiding students in finding their core values for their design practice, creating a connection to materials and building a bridge between art and science, traditional and new technologies and regaining a connection to nature to create a future for the generations coming after us.

Julia Moser sees her mission in re-thinking fashion and textile design practices and production processes towards a more sustainable and healthier future. Following the fact that nature knows how to produce colours without chemicals and harmful ingredients, she founded “Growing Patterns Living Pigments” and started to co-creating with pigment producing bacteria for dyeing textiles and involving them in the design process as well. With a focus on material innovation and bio design, she uses new technologies to find alternative ways of thinking design and design processes. Always remembering the indigenous tribe of the Kogi saying “You’re meant to work with technology, but if you do so, use technology that works with and not against nature”. Holding two Master degrees in textile.art.design and Fashion&Technology from the University of Art and Design Linz she’s currently working as a University Assistant at the Crafting Futures Lab. There she’s working on her PhD and guiding students in finding their core values for their design practice, creating a connection to materials and building a bridge between art and science, traditional and new technologies and regaining a connection to nature to create a future for the generations coming after us.

-

Sarah Ho

FabCafe Kyoto

Sarah graduated from the National University of Singapore with a BA in Communications and New Media. After which, she spent 3 years in Tinkertanker Pte Ltd, an edu-tech makerspace developing and implementing programs and kits for STEAM education in Singapore. In 2022, she graduated from Bunka Fashion Graduate School, where her research centered around zero-waste apparel production.

Bringing her enthusiasm for both education and connecting people, Sarah joined the Kyoto team in 2022 to expand the SPCS team and deepen engagement with the surrounding universities. She is particularly interested in zero-waste systems, tinkering and new mediums for cross-cultural exchange.

Sarah graduated from the National University of Singapore with a BA in Communications and New Media. After which, she spent 3 years in Tinkertanker Pte Ltd, an edu-tech makerspace developing and implementing programs and kits for STEAM education in Singapore. In 2022, she graduated from Bunka Fashion Graduate School, where her research centered around zero-waste apparel production.

Bringing her enthusiasm for both education and connecting people, Sarah joined the Kyoto team in 2022 to expand the SPCS team and deepen engagement with the surrounding universities. She is particularly interested in zero-waste systems, tinkering and new mediums for cross-cultural exchange.